Editor’s note: Today’s guest post is republished from Professor Aswath Damodaran’s blog, Musings on the Market.

I was a doctoral student at UCLA, in 1983 and 1984, when I was assigned to be research assistant to Professor Eugene Fama, who wisely abandoned the University of Chicago during the cold winters for the beaches and tennis courts of Southern California. Professor Fama won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2013, primarily for laying the foundations for efficient markets in this paper and refining them in his work in the decades after. The debate between passive and active investing that he and others at the University of Chicago initiated has been part of the landscape for more than four decades, with passionate advocates on both sides, but even the most ardent promoters of active investing have to admit that passive investing is winning the battle. In fact, the mutual fund industry seems to have realized that they face an existential threat not just to their growth but to their very existence and many of them are responding by cutting fees and offering passive investment choices.

Passive Investing is winning!

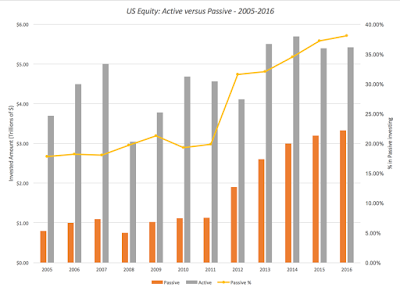

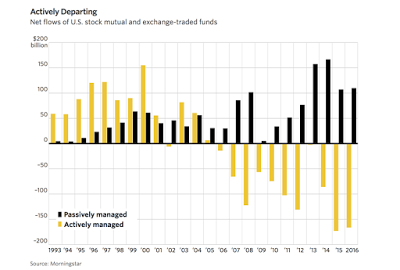

In 2016, passive investing accounted for approximately 40% of all institutional money in the equity market, more than doubling its share since 2005. Since 2008, the flight away from active investing has accelerated and the fund flows to active and passive investing during the last decade tell the story.

Aided and Abetted by Active Investing

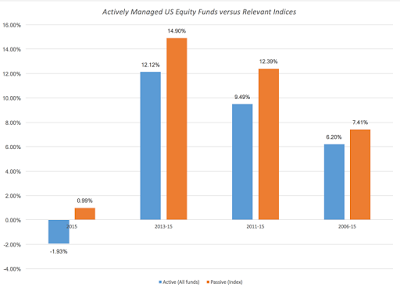

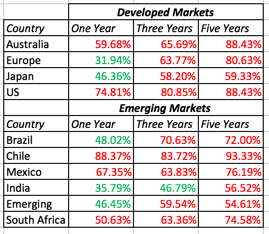

Before you attack me for being a dyed-in-the-wool efficient marketer, there is a simple mathematical reason why this statement has to be true. During 2015, for instance, about 40% of institutional money in equities was invested in index funds and ETFs and about 60% in active investing of all types. The money invested in index funds and ETFs will track the index, with a very small percentage (about 0.11%) going to cover the minimal transactions costs. Thus, active money managers have to start off with the recognition that they collectively cannot beat the index and that their costs (transactions and management fees) will have to come out of the index returns. Not surprisingly, therefore, active investors will collectively generate less than the index during every period and more than half of them will usually underperform the index. To back up the first statement, here are the median returns for all actively managed funds, relative to passive index funds for various time periods ending in 2015:

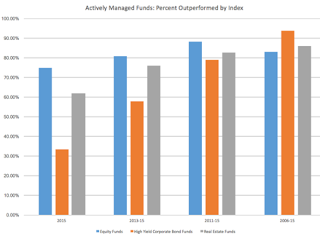

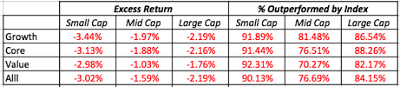

The standard defense that most active investors would offer to the critique that they collectively underperform the market is that the collective includes a lot of sub-standard active investors. I have spent a lifetime talking to active investors who contend that the group (hedge funds, value investors, Buffett followers) that they belong to is not part of the collective and that it is the other, less enlightened groups that are responsible for the sorry state of active investing. In fact, they are quick to point to evidence often unearthed by academics looking at past data that stocks with specific characteristics (low PE, low Price to book, high dividend yield or price/earnings momentum) have beaten the market (by generating returns higher than what you would expect on a risk-adjusted basis). Even if you conclude that these findings are right, and they are debatable, you cannot use them to defend active investing, since you can create passive investing vehicles (index funds of just low PE stocks or PBV stocks) that will deliver those excess returns at minimal costs. The question then becomes whether active investing with any investment style beats a passive counterpart with the same style. SPIVA, S&P’s excellent data service for chronicling the successes and failures of active investing, looks at the excess returns and the percent of active investors who fail to beat the index, broken down by style sub-group.

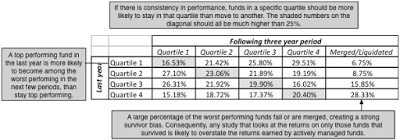

The third and final line of defense for active investors is that while they collectively underperform and that underperformance stretches across sub-groups, there is a subset of consistent winners who have found the magic ingredient for investment success. That last hope is dashed, though, when you look at the numbers. If there is consistent performance, you should see continuity in performance, with highly ranked funds staying highly ranked and poor performers staying poor. To see if that is the case, I looked at how portfolio managers ranked by quartile in one period did in the following three years:

Note that the numbers in the table, when you look at all US equity funds, suggest very little continuity in the process. In fact, the only number that is different from 25% (albeit only marginally significant on a statistical basis) is that transition from the first to the fourth quartile, with a higher incidence of movement across these two quartiles than any other two. That should not be surprising since managers who adopt the riskiest strategies will spend their time bouncing between the top and the bottom quartiles.

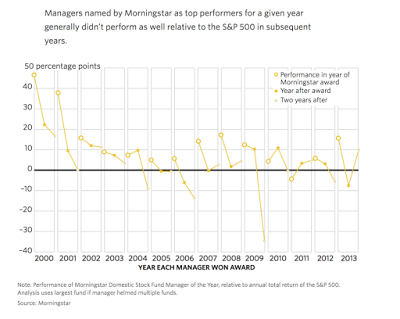

As your final defense of active investing, you may roll out a few legendary names, with Warren Buffett, Peter Lynch and the latest superstar manager in the news leading the list, but recognize that this is more an admission of the weakness of your argument than of its strength. In fact, successful though these investors have been, it becomes impossible to separate how much of their success has come from their investment philosophies, the periods of time when they operated and perhaps even luck. Again, drawing on the data, here is what Morningstar reports on the returns generated by their top mutual fund performer each year in the subsequent two years:

The What next?

- The active investing business will shrink: The fees charged for active money management will continue to decline, as they try to hold on to their remaining customers, generally older and more set in their ways. Notwithstanding these fee cuts, active money managers will continue to lose market share to ETFs and index funds as it becomes easier and easier to trade these options. The business will collectively be less profitable and hire fewer people as analysts, portfolio managers and support staff. If the last few decades are any indication, there will be periods where active money management will look like it is mounting a comeback but those will be intermittent.

- More disruption is coming: In a post on disruption, I noted that the businesses that are most ripe for disruption are ones where the business is big (in terms of dollars spent), the value added is small relative to the costs of running the business and where everyone involved (businesses and customers) is unhappy with the status quo. That description fits the active money management like a glove and it should come as no surprise that the next wave of disruption is coming from fintech companies that see opportunity in almost every facet of active money management, from financial advisory services to trading to portfolio management.

- Corporate Governance: As ETFs and index funds increasing dominate the investment landscape, the question of who will bear the burden of corporate governance at companies has risen to the surface. After all, passive investors have no incentive to challenge incumbent management at individual companies nor the capacity to do so, given their vast number of holdings. As evidence, the critics of passive investors point to the fact that Vanguard and Blackrock vote with management more than 90% of the time. I would be more sympathetic to this argument if the big active mutual fund families had been shareholder advocates in the first place, but their track record of voting with management has historically been just as bad as that of the passive investors.

- Information Efficiency: To the extent that active investors collect and process information, trying to find market mistakes, they play a role in keeping prices informative. This is the point that was being made, perhaps not artfully, by the Bernstein piece on how passive investing is worse than Marxism and will lead us to serfdom. I wish that they had fully digested the Grossman and Stiglitz paper that they quote, because the paper plays out this process to its logical limit. In summary, it concludes that if everyone believes that markets are efficient and invests accordingly (in index funds), markets would cease to be efficient because no one would be collecting information. Depressing, right? But Grossman and Stiglitz also used the key word (Impossibility) in the title, since as they noted, the process is self-correcting. If passive investing does grow to the point where prices are not informationally efficient, the payoff to active investing will rise to attract more of it. Rather than the Bataan death march to an arid information-free market monopolized by passive investing, what I see is a market where active investing will ebb and flow over time.

- Product Markets: There are some who argue that the growth of passive investing is reducing product market competition, increasing prices for customers, and they give two reasons. The first is that passive investors steer their money to the largest market cap companies and as a consequence, these companies can only get bigger. The second is that when two or more large companies in a sector are owned mostly by the same passive investors (say Blackrock and Vanguard), it is suggested that they are more likely to collude to maximize the collective profits to the owners. As evidence, they point to studies of the banking and airline businesses, which seem to find a correlation between passive investing and higher prices for consumers. I am not persuaded or even convinced about either of these effects, since having a lot of passive investors does not seem to provide protection against the rapid meltdown of value that you still sometimes observe at large market cap companies and most management teams that I interact with are blissfully unaware of which institutional investors hold their shares.

Making it personal

Disclosure

The foregoing article is reprinted in its entirety with the consent of the author, who is solely responsible for its content. The opinions expressed by the author therein are his own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Wealthfront Inc. or its management. All data and information provided in this article is for educational purposes only. Wealthfront Inc. makes no representations as to accuracy, completeness, currentness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article and will not be liable for any errors, omissions, or delays in this information or any losses, injuries, or damages arising from its display or use. All information is provided on an as-is basis. All trademarks, product names,company name, publisher name and their respective logos cited herein are the property of their respective owners. All copyrights belong to their respective owners. Images and text owned by other copyright holders are used here under the guidelines of the Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Nothing in this article should be construed as tax advice, a solicitation or offer, or recommendation, to buy or sell any security. This article is not intended as investment advice, and Wealthfront Inc. does not represent in any manner that the circumstances described herein will result in any particular outcome. Investment advisory services are only provided to investors who become Wealthfront Inc. clients. For more information, please visit www.wealthfront.com or see our Full Disclosure.

About the author(s)

Professorr Aswath Damodaran holds the Kerschner Family Chair in Finance Education and is Professor of Finance at New York University Stern School of Business. Prior to arriving at Stern, he lectured in Finance at the University of California, Berkeley. Professor Damodaran's contributions to the field of Finance have been recognized many times over. He has been the recipient of Giblin, Glucksman, and Heyman Fellowships, a David Margolis Teaching Excellence Fellowship, and the Richard L. Rosenthal Award for Innovation in Investment Management and Corporate Finance. His skill and enthusiasm in the classroom garnered him the Schools of Business Excellence in Teaching Award in 1988, and the Distinguished Teaching award from NYU in 1990. His student accolades are no less impressive: he has been voted "Professor of the Year" by the graduating M.B.A. class five times during his career at NYU. In addition to myriad publications in academic journals, Professor Damodaran is the author of several highly-regarded and widely-used academic texts on Valuation, Corporate Finance, and Investment Management. Professor Damodaran currently teaches Corporate Finance and Equity Instruments & Markets. His research interests include Information and Prices, Real Estate, and Valuation. Professor Damodaran received a B.A. in Accounting from Madras University and a M.S. in Management from the Indian Institute of Management. He earned an M.B.A. (1981) and then Ph.D. (1985), both in Finance, from the University of California, Los Angeles. View all posts by Professor Aswath Damodaran