Last week I showed some of the different ways to think about financial aid as a means to understand -- and reduce -- the out-of-pocket costs of a particular college. This week, I want to share some of our research around some additional ways to reduce college costs. Several of these strategies have trade-offs, so it’s important for parents and students to start thinking early about their options. However, much like with financial aid, empowering yourself with knowledge will put you in a better position to help your son or daughter earn a college degree without some of the paralyzing costs.

Last week I showed some of the different ways to think about financial aid as a means to understand — and reduce — the out-of-pocket costs of a particular college. This week, I want to share some of our research around some additional ways to reduce college costs. Several of these strategies have trade-offs, so it’s important for parents and students to start thinking early about their options. However, much like with financial aid, empowering yourself with knowledge will put you in a better position to help your son or daughter earn a college degree without some of the paralyzing costs.

Home Sweet Home

Living on-campus has its cultural benefits, but it also comes with a lot of additional expenses. On average room and board costs about $8,900 per year at 4-year colleges, up about 40% since 2005. For context, those costs have risen considerably faster than the overall rate of inflation.[1] The average full cost of an in-state, public university is about $22,000, but living at home can shave about 40% off the top.[2] As a result, more students are opting to live with their parents and commute to campus. In fact, according to surveys by Sallie Mae about 37% of four-year students and 71% of two-year community college students are commuters.

The downside of living at home for some students is the possibility of missing out on the “traditional” college social experience. It can also mean less independence from parents and feeling like they haven’t really transitioned from high school. Ironically, though, living at home could actually mean even more independence later. This is because of the long-term deleterious effects of increasing student debt.

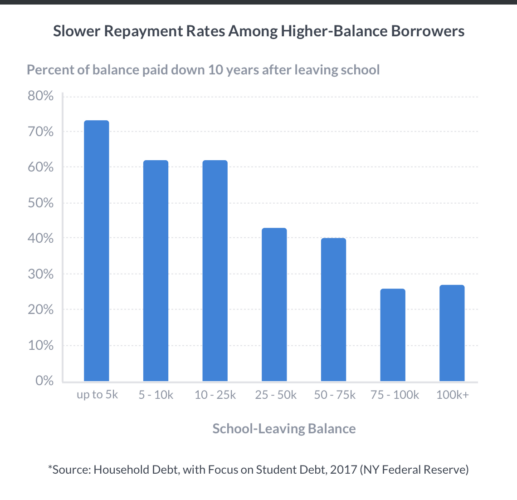

According to Sallie Mae, total student loan debt has soared 199% to $1.44 trillion since 1996. On average, college students cover 13% of their costs through student loans. The average student loan balance at the time of graduation is $34,000, up 70% from 2006 to 2015. Worse, over 20 years the accumulated cost of interest payments can double or triple the original cost of that. So with an average room and board cost of $8,900 a year for 4-year colleges, living at home can help offset costs and significantly reduce a graduate’s amount of debt.

The Two-Year Itch

Community colleges are some of the biggest hidden bargains in higher education, especially for students who use them to earn the first half of a four-year degree. The median cost of community college is $13,400 a year, compared to the aforementioned $22,000 for in-state students at a public university.[3] That’s a potential savings of $8,600 per year, or $17,200 for those students who transfer after two years and get their bachelor’s degree at a four-year state institution.

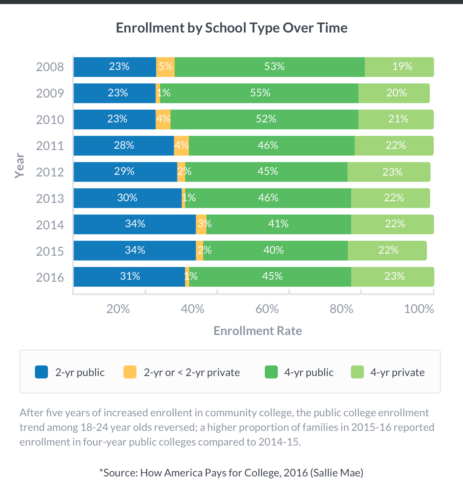

Nationwide, the share of students attending community college has jumped markedly since the recession, from 23% in 2009 to 31% in 2015. Meanwhile, the share of community college students who transfer to four-year universities has almost doubled, from less than 5% in 2006 to more than 9% in 2014. In fact, many states actively encourage this strategy by coordinating efforts between state junior and four-year colleges to ensure students moving from a two-year school can transfer all of their course credits and avoid any setbacks.

The Virtual Campus

Online education has soared over the past decade, and the technology certainly offers tremendous opportunities for cost-cutting. Penn State, a public state university, charges $14,200 a year for online tuition, compared to $17,900 for on-campus tuition, giving the online degree program an edge when room and board costs are omitted from both tracks. But when you consider room and board costs, Penn State comes in at almost $33,000 per year all-in for in-state, on-campus tuition, making the savings associated with online degree programs even more significant.

However, not all online programs are a bargain. The University of Phoenix, a for-profit online college, costs $55,400 per year for a bachelor of science in business, compared to the aforementioned $14,200 Penn State charges for the same virtual program. In other words, a four-year degree earned online from the University of Phoenix is 290% more than the Penn State equivalent. So the message is obvious when it comes to online degree programs: buyer beware.

But it’s not just the University of Phoenix — students at non-profit colleges are often charged a premium for the convenience of learning online. Some public universities, struggling with declining government support, have begun systematically charging higher tuition and fees for the convenience associated with online learning. In 2012 the Western Cooperative for Educational Telecommunications surveyed 199 colleges and found that early a third of all respondents reported charging a premium for online tuition. The bottom line is that most online degree students can expect to pay 5-10% more for the privilege of a commute-free degree.

The Best Way to Save: Graduate on Time

Delayed graduation has become an epidemic in the United States, and those delays come with exceptionally high costs. In fact, earning a college degree within four years is now the exception rather than the rule. According to this report from Complete College America, an organization formed by governors from around the nation, only 50 out of 580 state universities have four-year graduation rates of 50% or higher.

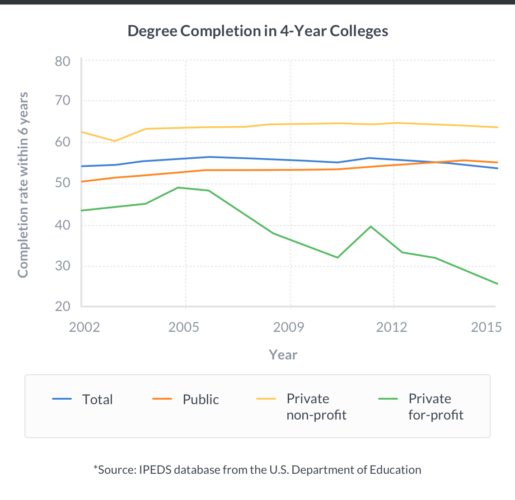

At public two-year colleges, fewer than one-quarter of students graduate on time. The record at private, for-profit colleges, like the University of Phoenix, are considerably worse. Federal data shows that the share of students at for-profit institutions who graduate within six years has plunged from more than 40% in 2002 to well below 30% in 2015.[4]

To be fair, some of this is out of students’ control. Cost-cutting at many public institutions has made it harder for students to get into their required classes, often forcing them to wait an extra semester simply because of scheduling challenges. However, the report also finds that many delays are self-inflicted. Only half of students at four-year colleges take enough credits each semester to graduate on time. Many lose time “wandering the catalog”, taking classes they don’t really need, or switching majors. Students also lose time by switching schools; on average about half of all transfer students lose some of their previous course credits when moving to a new college.

Some Final Thoughts

As expensive as college is, parents and students have big opportunities to think creatively to help dramatically reduce the costs. Some strategies, such as living at home and commuting to school, might have some initial trade-offs, but the long-term financial benefits are significant. But the key is to think ahead and develop a plan that will lead to an on-time graduation, which is the lesser known culprit to increasing debt. Naturally the best way to prepare for any scenario is to start saving today. However, understanding and investigating the range of options early will also help enable a more optimal — and likely much cheaper — four years of college.

__________________

[1] Calculated using the IPEDS database from the U.S. Department of Education.

[2] These are calculated using the same IPEDS database.

[3] Calculated using the IPEDS database from the U.S. Department of Education.

[4] Calculated using the IPEDS database from the U.S. Department of Education.

Disclosure

Nothing in this blog should be construed as tax advice, a solicitation or offer, or recommendation, to buy or sell any security. Financial advisory services are only provided to investors who become Wealthfront Inc. clients pursuant to a written agreement, which investors are urged to read carefully, that is available at www.wealthfront.com. For more information please visit www.wealthfront.com or see our Full Disclosure. While the data Wealthfront uses from third parties is believed to be reliable, Wealthfront does not guarantee the accuracy of the information.

About the author(s)

Andy Rachleff is Wealthfront's co-founder and Executive Chairman. He serves as a member of the board of trustees and chairman of the endowment investment committee for University of Pennsylvania and as a member of the faculty at Stanford Graduate School of Business, where he teaches courses on technology entrepreneurship. Prior to Wealthfront, Andy co-founded and was general partner of Benchmark Capital, where he was responsible for investing in a number of successful companies including Equinix, Juniper Networks, and Opsware. He also spent ten years as a general partner with Merrill, Pickard, Anderson & Eyre (MPAE). Andy earned his BS from University of Pennsylvania and his MBA from Stanford Graduate School of Business. View all posts by Andy Rachleff