Investment pundits – ourselves included – write a lot about how checking your portfolio too frequently is hazardous to both your financial and mental health. The evidence is overwhelming that those who check their portfolios on a daily basis tend to underperform those who check their portfolios less frequently.

The reason is simple: On any given day, there’s almost a 50-50 chance the market will be up or down. Because people dislike losses more than than they enjoy gains – a behavioral finding known as loss aversion – people who check their portfolios daily find the process painful. And just like your gut reaction to pain is to draw away from the source of that pain, your gut reaction to seeing an investment lose money is to make a change. To sell. To panic. To act.

Changing your portfolio, or market timing as our Chief Investment Officer Dr. Burton Malkiel calls it, is an investor’s Most Serious Mistake.

So what’s the solution? Just check your portfolio less often, right?

Unfortunately, things really don’t get much better if you check less frequently.

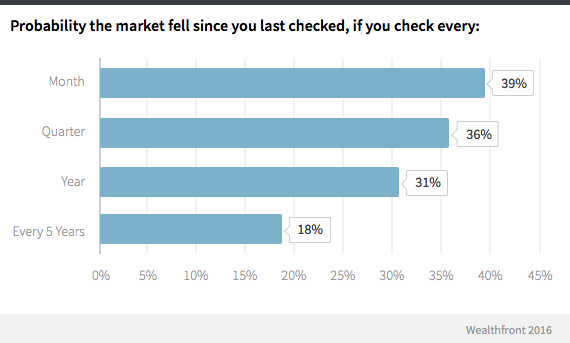

We looked at historical market data going back as far as possible (1871, to be precise) to ask what the probability is that the market is down depending on how often you check.

Over the last 144 years, there was a 39% probability that an investor who checked her portfolio once a month would see the market down. Even if she looked once a year, there’s still a 31% chance that the market will be in the red.

Credit goes to Justin Wolfers for inspiring this chart. The data come from Professor Robert Shiller’s Yale University website.

What’s an investor to do? Even if you control your curiosity and only check on your investments once a year, you’re going to spend a third of your life fuming at the results!

It isn’t your fault: The human body simply isn’t built for making good investment decisions

Loss aversion isn’t driven by mental weakness; it’s a biological phenomenon. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed that loss aversion is primarily driven by the amygdalae, two almond-shaped parts of the brain that are key components our limbic system, which is responsible for most of our emotional life. The study found that people with damaged amygdalae aren’t loss averse.

Does that make you want to get rid of your amygdalae?

Scholars of evolutionary psychology actually believe that loss aversion is one of the reasons we are here today. Recent research suggests loss aversion became an important part of human nature tens of thousands of years ago, when we were foragers (McDermott, Fowler, and Smirnov, 2008). Running out of food was fatal, so if our ancestors ended up in a location where there wasn’t enough food they had to react quickly and change plans. Those who weren’t loss averse didn’t survive.

What’s important to realize is that a loss in your investment portfolio isn’t the same as running out of food. Running out of food is an immediate problem; a temporary loss in your investment portfolio isn’t.

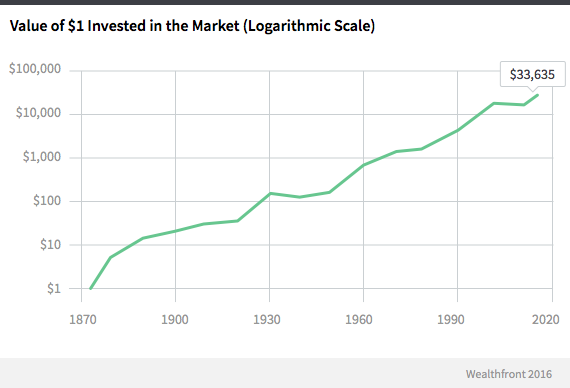

In fact, it’s a problem that tends to even itself out over time. As the chart below shows, $1 invested in 1871 is worth nearly $34,000 today. It just took some bumps along the way.

At Wealthfront we try to make very clear that our investment approach is only appropriate for the long term. Please see What Defines Long Term Investing for more information on what that means.

The best investors know they must have a long term perspective and find ways to make investing less emotional.

What to do? Find strategies to divorce emotion from investing

Research shows there is something you can do to make it easier. Specifically, the best approach is to make a single rational plan and commit to it, and then use that commitment to ride out the emotional ups and downs.

That means doing things like:

- Setting up a repeating deposit, so that you’re always investing … whether the market is up short-term or down.

- Committing to an automated investment service or solid financial advisor … to take your hands off the trigger.

- Training yourself to think about market pullbacks as opportunities to buy more at lower prices … to prepare yourself for the inevitable.

It isn’t easy, bucking basic biology. But if you take a moment while you’re calm to firmly commit yourself to investing early and often, it will pay off long-term.

On our end, we’re here to help. We work every day to improve our service to help guide you in your desired direction. That means requiring you to do less and warning you before you make a mistake. We’ve optimized our site to make it seamless, and we take care of the annoying stuff, like automated rebalancing and dividend reinvestment, so you don’t have to check-in as often. And we’ve created what we believe is the best automated daily tax-loss harvesting process to soften the bumps from the inevitable pullbacks.

To paraphrase an old saying: Investing is simple. It just isn’t easy.

References

De Martino, Benedetto, Camerer, Colin F., Adolph, Ralphs. (2009) Amygdala Damage Eliminates Monetary Loss Aversion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(8): 3788—3792.

McDermott, R., Fowler, James H., Smirnov, Oleg. (2008) On the Evolutionary Origin of Prospect Theory Preferences. The Journal of Politics, 70(2): 335—350.

Shiller, Robert. U.S. Stock Markets 1871-Present and CAPE Ratio. Retrieved Dec 17, 2015.

Disclosure

Nothing in this article should be construed as tax advice, a solicitation or offer, or recommendation, to buy or sell any security. The information provided here is for educational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. While the data Wealthfront uses from third parties is believed to be reliable, Wealthfront does not guarantee the accuracy of the information. There is a potential for loss as well as gain. Actual investors on Wealthfront may experience different results from the results shown.

About the author(s)

Duncan is a member of Wealthfront’s research team, where he leverages insights from data and behavioral economic theory to improve Wealthfront’s products. He holds a PhD in Business Economics, an AM in Economics, and an AB in Applied Mathematics, all from Harvard University. View all posts by Duncan Gilchrist, PhD