Over the past five years we have written numerous posts to try to convince our readers that timing the market doesn’t make sense. We’ve provided data that proves the average retail investor loses a significant amount of money from doing what feels right: buying when the market rises and selling when it declines. The good news is that the message must be sinking in, as we’ve seen an uptick in inquiries to our client service team asking whether they should wait to invest more until the market goes down. In theory this makes great sense, but in reality it’s extremely difficult to execute. So today we’ll help spell out the challenges of “buying on the dip.”

How Low Can it Go?

So how do you know at what point to invest when the market declines? Unfortunately you can’t tell with any certainty when the market is likely to hit bottom. For example, you may have thought that September 2008 was the “dip” on which to buy, but in fact the market continued to decline another six months until March 2009. The same was true when the Internet bubble popped, except hitting the actual bottom took even longer. Buying on the dips takes considerable guts because you really don’t know if the market has bottomed out or if you’re catching a falling knife. Advocates of technical analysis believe they can determine when the market has reached bottom, but no peer reviewed academic research exists to support their claims.

The Opportunity Cost

If you’re going to invest when the market declines you need to have uninvested cash. But if you are sitting on cash then you run the risk that the market will go up while you’re waiting on the sidelines. On average the stock market increases over time, which means it’s usually a bad decision to be out of the market.

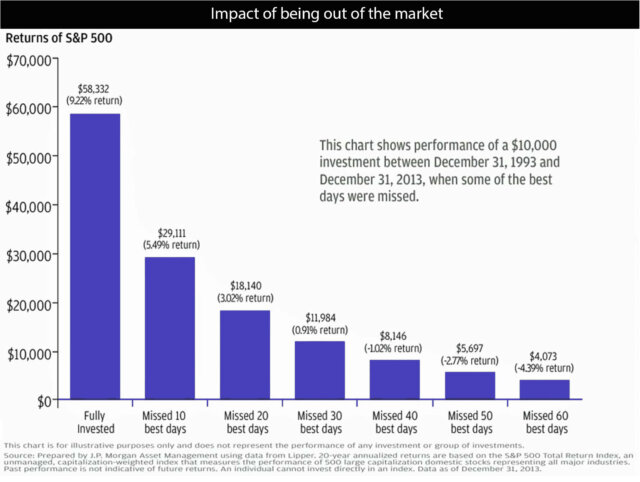

To reinforce this idea, let’s look at some extreme-but-illustrative examples of how much it could have cost an investor to miss some key days of surging prices. In the table below, JP Morgan Asset Management evaluated the performance of the S&P 500 over 20 years from December 31, 1993 to December 31, 2013 which represents more than 5,000 days during which the markets were open. If you stayed invested the entire time, a $10,000 investment would have multiplied to $58,332 – a 9.2% annual return.

Source: JP Morgan

However if you were not invested during the 10 best performing days (which equates to less than 1/500th of the total time) the total value of your portfolio would have dropped to $29,111, wiping out almost exactly half of the returns you would have seen if you stayed the course over those 20 years.

If you missed the 40 best days (less than 1% of the 20-year time period), your 9.2% average annual gain would have converted into a loss of $854. So the takeaway is patience and staying invested for the long term are crucial for the greatest long-term benefit. This applies to any interpretation of a dip, from waiting for “down day” to waiting for a “decline of X%.”

Many investors believe they can predict when markets are going to crash. Further, many believe they can determine when markets are at a temporary peak so they can cash out, lock in profits, and avoid the market downturn. Even if an investor can withdraw before a market downturn, she will still face the challenge of market timing when getting back in on the market (not to mention the taxes associated with cashing out).

What About a Diversified Portfolio?

If you want to wait for a market pullback to invest, then putting that money in a diversified portfolio isn’t the best approach. A diversified portfolio holds relatively non-correlated asset classes, meaning on any given day the most likely scenario is that some asset classes will be up and some will be down. Even if you could time the US stock market correctly, you’d be buying some other asset classes that might trade in the other direction.

The Takeaway

You can try, but markets simply cannot be timed in any form. In fact if you could actually consistently time the market you’d probably be running one of the world’s most successful hedge funds. So instead of trying to time markets or worry about the best time to make a deposit, you should focus on the three things within your investing control that can make a difference on your outcome: maximizing diversification, minimizing fees and minimizing taxes.

Disclosure

The information contained in this communication is provided for general informational purposes only, and should not be construed as investment advice. Nothing in this communication should be construed as an offer, recommendation, or solicitation to buy or sell any security. Any links provided to other server sites are offered as a matter of convenience and are not intended to imply that Wealthfront Advisers or its affiliates endorses, sponsors, promotes and/or is affiliated with the owners of or participants in those sites, or endorses any information contained on those sites, unless expressly stated otherwise.

Investment advisory services are provided by Wealthfront Advisors LLC (“Wealthfront Advisers”), an SEC-registered investment adviser, and brokerage products and services, are provided by Wealthfront Brokerage LLC (formerly known as Wealthfront Brokerage Corporation), member FINRA / SIPC. Wealthfront Software LLC (“Wealthfront”) offers a free software-based financial advice engine that delivers automated financial planning tools to help users achieve better outcomes.

All investing involves risk, including the possible loss of money you invest, and past performance does not guarantee future performance. Wealthfront Advisers and its affiliates rely on information from various sources believed to be reliable, including clients and third parties, but cannot guarantee the accuracy and completeness of that information. For more information, please visit www.wealthfront.com or see our Full Disclosure

Wealthfront Advisers, Wealthfront Brokerage and Wealthfront are wholly owned subsidiaries of Wealthfront Corporation.

© 2020 Wealthfront Corporation. All rights reserved.

About the author(s)

Andy Rachleff is Wealthfront's co-founder and Executive Chairman. He serves as a member of the board of trustees and chairman of the endowment investment committee for University of Pennsylvania and as a member of the faculty at Stanford Graduate School of Business, where he teaches courses on technology entrepreneurship. Prior to Wealthfront, Andy co-founded and was general partner of Benchmark Capital, where he was responsible for investing in a number of successful companies including Equinix, Juniper Networks, and Opsware. He also spent ten years as a general partner with Merrill, Pickard, Anderson & Eyre (MPAE). Andy earned his BS from University of Pennsylvania and his MBA from Stanford Graduate School of Business. View all posts by Andy Rachleff