Buying when the market rises and selling when it declines is human nature. It just feels like the right thing to do. But like most things related to investing, what feels right is the opposite of what you should do. So today I’ll use some data — and a little tough love — to prove that leading with emotion and trying to time the market is actually careless behavior.

History Repeats Itself

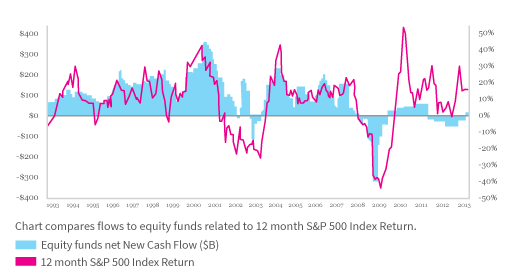

If we look back over time we can see that big market fluctuations result in consistent poor behavior. When prices are high and returns are good, money tends to flow into equity mutual funds; when prices are low, investors typically make net withdrawals of funds. The chart below looks at the flow of money into and out of equity mutual funds (the shaded histograms) on the 12-month returns of the Standard and Poor’s 500 index (the solid line) over the course of two decades.

Source: Investment Company Institute

Some of the biggest peaks and drops coincide with some of the more emotionally charged market periods. For example, more new money was invested in equity mutual funds than ever before in the first quarter of 2000, which coincided with the top of the Internet bubble. Then in the fourth quarter of 2002, which turned out to be the market bottom after a sharp decline in stock prices, investors pulled large amounts of money out of equity mutual funds. Fast forward to the third quarter of 2008, during the worst of the recent financial crises in recent history, and investors redeemed unprecedented amounts of equity mutual funds. The market is unpredictable, so we’ll always have big swings. And while some people might get lucky timing the market, it’s just that — luck.

Money vs. Time

We see this behavior among some of our own clients, who make occasional deposits to try and capitalize on upward market swings. Again, this is human nature, so another way to make the argument and help change that behavior is to look at the money-weighted return of frequent depositors versus their time-weighted return.

A money-weighted return takes into consideration the timing of your investments, and the return is calculated based on when you invest add-on deposits or make a withdrawal. In contrast, time-weighted returns assigns each period’s return the same weight, regardless of how much money was invested or taken out. It’s effectively a measure of your compounded return (or the product of all your daily returns), and does not take into consideration when you make your add on investments.

For example, two investors have a portfolio valued at $100,000. The first investor contributes an additional $25,000 on August 15th, while second investor withdraws $25,000 on the same date, and then the market subsequently has a downturn. Both investors would have exactly the same time-weighted return, even though the first made a large contribution right before a downturn, and the second made a large withdrawal. Alternatively, the first investor would have a significantly lower money-weighted return because he made a large contribution prior to the downturn. The money-weighted return for the second investor would be significantly higher because she made a large withdrawal prior to the period of poorer market performance. Thus, time-weighted returns are the superior way to evaluate your investment manager because he or she doesn’t have control over your cash flows, and money weighted return is the better way to test your ability to time the market.

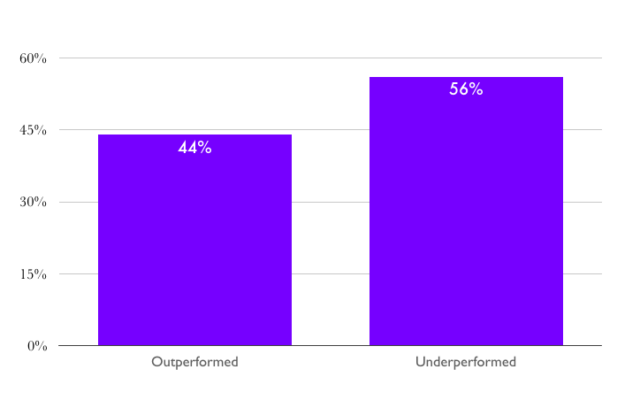

The chart below compares the money weighted return of our clients who made at least three add on deposits on a non-scheduled basis with their time weighted return since inception.

Source: Wealthfront

As you can see, 56% of these clients had money-weighted returns that underperformed compared to their time-weighted return, and only 44% had money-weighted returns that were superior. In other words, more than half our clients destroyed their own value by trying to time the market by adding or withdrawing money in response to market swings and the difference between the percentage that underperformed and outperformed is statistically significant. Our clients who chose to time the market would have been better served if they scheduled a recurring deposit to ensure they invested the same amount every period. That approach better approximates your time-weighted return. And while it might take longer to put your money to work, you’re statistically more likely to earn a better return.

Final Thoughts

Several empirical studies have tried to measure the cost of bad timing decisions. They all agree that active investors tend to do much worse than a buy and hold investor who avoided market timing altogether. A well-known study of the so-called “behavior gap” by DALBAR Associates estimates that it may be as large as 5% annually over the past 20 years. Other studies have estimated somewhat smaller gaps, but they all agree that this kind of investor behavior is harmful and extremely costly. Unfortunately, though, human behavior is hard to change. But at Wealthfront, you can count on us to keep banging the “slow-and-steady” drum. It’s a contrarian view, but in this case being contrarian makes you a better investor.

Disclosure

Nothing in this communication should be construed as an offer, recommendation, or solicitation to buy or sell any security. Wealthfront’s financial advisory and planning services, provided to investors who become clients pursuant to a written agreement, are designed to aid our clients in preparing for their financial futures and allow them to personalize their assumptions for their portfolios. Additionally, Wealthfront and its affiliates do not provide tax advice and investors are encouraged to consult with their personal tax advisors.

All investing involves risk, including the possible loss of money you invest, and past performance does not guarantee future performance. Wealthfront and its affiliates rely on information from various sources believed to be reliable, including clients and third parties, but cannot guarantee the accuracy and completeness of that information.

The S&P 500® (“Index”) is an index of 500 stocks seen as a leading indicator of U.S. equities and a reflection of the performance of the large cap universe, made up of companies selected by economists. The S&P 500 is a market value weighted index and one of the common benchmarks for the U.S. stock market.

The S&P 500 (“Index”) is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates and has been licensed for use by Wealthfront. Copyright © 2015 by S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a subsidiary of the McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution, reproduction and/or photocopying in whole or in part are prohibited Index Data Services Attachment without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. For more information on any of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC’s indices please visit www.spdji.com. S&P® is a registered trademark of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC and Dow Jones® is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC. Neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC, their affiliates nor their third party licensors make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the ability of any index to accurately represent the asset class or market sector that it purports to represent and neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC, their affiliates nor their third party licensors shall have any liability for any errors, omissions, or interruptions of any index or the data included therein.

About the author(s)

Andy Rachleff is Wealthfront's co-founder and Executive Chairman. He serves as a member of the board of trustees and chairman of the endowment investment committee for University of Pennsylvania and as a member of the faculty at Stanford Graduate School of Business, where he teaches courses on technology entrepreneurship. Prior to Wealthfront, Andy co-founded and was general partner of Benchmark Capital, where he was responsible for investing in a number of successful companies including Equinix, Juniper Networks, and Opsware. He also spent ten years as a general partner with Merrill, Pickard, Anderson & Eyre (MPAE). Andy earned his BS from University of Pennsylvania and his MBA from Stanford Graduate School of Business. View all posts by Andy Rachleff