Tax-wise, 2012 is an unusual year. Most experts are predicting, with an unusual amount of certainty based on the political climate and the state of the deficit, that the long-term capital gains tax rate will increase in 2013, to 20% from 15%. In 2012, Congress added an additional 3.8% capital gains tax as part of Obamacare.

Therefore, the total could go to 23.8% from 15%. This means someone selling a long-term capital gain in 2013 would pay an additional 8.8% on those gains compared with someone selling in 2012, unless an unforeseen compromise during the fiscal cliff negotiations averts the increase.

There’s a saying among tax accountants that the tax tail shouldn’t wag the dog; the tax consequences of an action usually matter less than the other consequences that you care about. And it’s usually a fruitless endeavor to try to predict tax policy.

In this case, however, the scenario seems certain enough and the increase is large enough that you should be thinking through your choices, especially if you plan to liquidate some or all of your portfolio within the next seven years. If your investment advisor hasn’t suggested a review of your portfolio to see if selling now or harvesting gains and reinvesting makes sense, you should ask him or her to review your account.

We’ve analyzed a few options for our clients and are sharing the results of our analysis below.

There is one clear-cut case for acting now – it’s already reflected in the way people are dashing to sell their businesses and real estate holdings. If you intended to liquidate an investment within the next year or sell a significant portion to make a big purchase, like a house, and the investment appreciated over more than a year, it makes sense to accelerate your plans. In other words, you should strongly consider selling before the end of this year instead of waiting until next year.

If you intended to liquidate an investment within the next year, and it has appreciated over more than a year, it may make sense to accelerate your plans.

If you plan to liquidate a large amount of company stock that you’ve held more than a year in order to diversify your holdings because your company went public this year, you should consider taking that action before the end of the year. Decisions about how much to diversify a big holding in your company’s stock are complicated and depend on the extent to which you believe your company’s stock will appreciate over time. If you’ve already decided to diversify, you may want to consider accelerating that action.

For people who want to leave their money invested, the question is more complicated. Does it make sense to sell now, pay the current capital gains tax rate, and reinvest the money? In other words, take some of a gain on your holdings now, to take advantage of lower capital gains tax rates? That is a process called “capital gains harvesting” or “tax gain harvesting,” the flip side of tax-loss harvesting, the service we offer to clients with portfolios of $100,000 or more. If you’re harvesting gains, you’ll split the gain in two, so that you pay part of the gain at the lower tax rate and part at the higher.

Under a tax gain harvesting scenario, you’ll pay the capital gains tax on your initial gain at a lower rate. You’ll also pay capital gains tax on any subsequent gain later at the future tax rate when you liquidate the securities.

A primer on taxes in your portfolio

Before we get into the details, it might be useful to do a quick review of how Uncle Sam treats your investments. The gain on your investments held over more than one year is subject to the long-term capital gains tax. You pay ordinary income tax rate for short-term capital gains (on investments held for less than a year). You pay the dividend tax rate on dividends, and the ordinary income tax rate on your interest from bonds. For most people, the ordinary income tax rate is much higher than their long-term capital gains tax rate.

It’s hard to control your ordinary income tax and impossible to control your dividend tax, but you can control the timing (and in 2012-2013, the amount) of your long-term capital gains taxes by controlling the timing of when you sell the investment for a gain or loss.

Many of our clients care deeply about this issue because they hold significant amounts of stock and options. The holding period for your company stock begins the day you exercise your options. If you exercised your stock more than a year ago, and your company went public, you are likely to have a huge gain on your stock, one that’s subject to the long-term capital gains tax.

When does tax gain harvesting make sense?

You don’t owe any taxes on capital gains as long as they stay unrealized paper gains. Generally, people want to delay paying taxes as long as possible to allow the money to continue to grow by compounding. In order for it to make sense to realize your capital gains, the tax savings between 2012 and a later year would need to outweigh the benefit of compounding for a larger amount over time. One side note: if you take long-term gains, reinvest and then sell in less than a year, you’ll then pay short-term capital gains on your second set of gains, which may defeat the purpose.

First, let’s talk about the actual mechanism we used to make this analysis. We’re using round numbers just so you can see how tax gain harvesting works.

Let’s say I hold 100 shares of my company stock, which I bought when they were worth $50 per share, and more than a year later are now trading at $70 per share. I have an unrealized gain of $2,000.

If I sold my position before year-end, then the $2,000 would become a realized long-term gain, and I’d have to pay taxes on it in April. Assuming I don’t immediately need the money, I could buy back those same 100 shares five minutes later and I’d have the same investments as before, but they would have a higher cost basis. The cost of realizing the gain now would be the commission on the two trades and maybe a few cents per share change in price.

Two years later, if I sell my company stock for $80 per share, I only have a gain of $1,000, because I’m counting from my new $70 cost. If I hadn’t done the trade in 2012, I’d have a $3,000 gain.

So if you take your gains and pay taxes now, you’d pay $300 ($2,000 X 15%) in 2012 and $238 ($1,000 X 23.8%) in 2014 for a total of $538. If you don’t take your gains now, you’d end up paying $714 ($3,000 X 23.8%) in 2014.

Is this always the case? Not necessarily. If we expect to hold on to investments for 10 years, and at that point they are worth $200/share, the long-term capital gains taxes would be $3,570 on a gain of $15,000 for a total after-tax proceeds of $16,430. If we took gains today, then we should really be talking about reinvesting the money after taking out the taxes. So instead of selling $7,000 worth and then buying back $7,000, we’d only be buying back $6,700, which means that 10 years from now, the value would only be $19,143, or $16,181 after taxes.

Therefore paying taxes early is a bad idea if you intend to hold the investments 10 years or longer.

This is a general consequence of the fact that investment returns generally compound over time, while taxes are a fixed percentage of the gains.

Two scenarios

Let’s take some actual numbers into account. We have two scenarios:

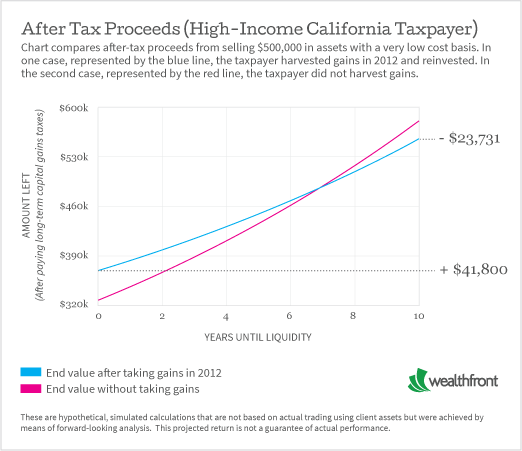

Let’s say you are a high-income California taxpayer who is sitting on a pile of stock worth $500,000, which has appreciated 95% and is subject to the long-term capital gains tax. If you expect to sell within two years, you are better off harvesting gains now. You could save more than $30,000. If you expect to stay invested for more than seven years, you’d be better off not selling in 2012.

The point at which the lines cross in the chart below shows you the point at which it no longer makes sense to harvest gains: Year 7.

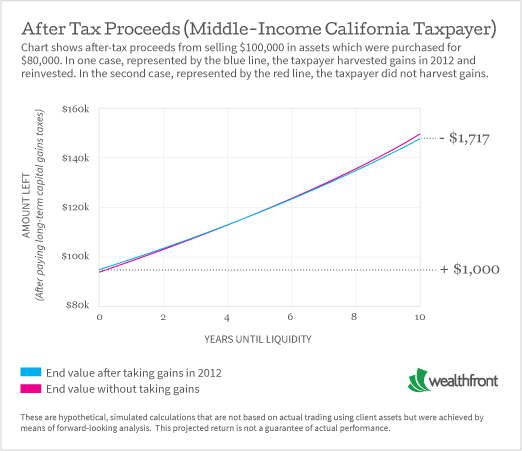

In the second scenario let’s say you are a middle income California taxpayer with a diversified portfolio that has some appreciation. Your portfolio is worth $100,000 and has appreciated 25%. Because your income is below $200,000 (including the capital gains) you are not subject to the 3.8% Obamacare tax.

In this case, the benefits are more modest. If you expect to need the money within the next two years, you could save half a percent by taking your gains today. Any benefits disappear if you plan to stay invested for more than four years.

The point at which the lines cross in the chart below shows you the point at which it no longer makes sense to harvest gains: Year 5.

As you can see from the analysis above, the benefits of accelerating your selling schedule, or harvesting gains might be significant. If you haven’t yet discussed this with your advisor or personal tax accountant, you should.

Disclosure

This material has been prepared for informational purposes only. It does not provide nor is it intended to provide personal investment advice, recommendations, or tax advice. We based our material on reliable third-party reports regarding upcoming changes to tax laws, but we do not guarantee that the accuracy of these reports or how these changes may affect your personal situation. You should consult your personal tax advisor regarding the tax information presented here based on your particular circumstances. This material was not prepared to be used, and it cannot be used, by any investor to avoid penalties or interest.

Investors and their personal tax advisors are responsible for how the transactions conducted in an account are reported to the IRS or any other taxing authority on the investor’s personal tax returns. Wealthfront assumes no responsibility for the tax consequences to any investor of any transaction.

The graphs pertaining to high-income California taxpayers (12.3% tax bracket) and the middle-income California taxpayers (9.3% tax bracket) are based on our own forward-looking calculations. We use these calculations to provide a basis for estimating the tax consequences of one tax strategy. We assume a hypothetical annual fixed return of 6%. We do not take into consideration AMT, phase-outs, or other aspects of taxes beyond long-term capital gains including possible changes to the tax code before April; nor do we consider expenses, fees or commissions. We also do not consider market fluctuations or other material economic factors. Investments are subject to market fluctuations and material economic conditions and may lose value. The projected return is not a guarantee of actual performance.