Financial decisions are among life’s most complex decisions, which is why many people turn to professional financial advisers for help. While the profession has its supporters, it also has a large group of critics. Most of these critics argue that advisers don’t truly act in your best interest as true “fiduciaries,” but instead, will simply talk you into doing whatever is most profitable for them personally. Some even doubt whether advisers are capable of offering sound advice, even if they wanted to.

So what’s the primary problem with financial advisers: Misaligned incentives, or misguided beliefs? A surprising study by three economists gives emphatic support to the latter position.

After surveying more than 4,000 Canadian financial advisers and half a million of their clients, the academics concluded that the vast majority of advisers made many of the classic rookie mistakes of personal finance. They relied on expensive actively managed mutual funds instead of the low-cost index funds, which are proven to make for a better portfolio. And they also attempted to “time the market” by jumping in and out of mutual funds.

At Least They’re Consistent

And here is the most surprising part of the study. The financial advisers didn’t just subject their clients to their bad advice. They also followed it themselves, in their own portfolios, and even did so after making career moves to other professions.

Of course, both advisers and clients ended up poorer as a result. The economists found that the bad decision to use high fee, actively managed mutual funds reduced returns by 2.4% a year for both adviser and client portfolios. That may not sound like much, but over the lifetime of a portfolio, it can be devastating. For example, with a 60-year investment horizon, typical for today’s 30-something investors, an annual reduction of 2.4% per year leads to nearly 80% of the client’s initial wealth being paid out in fees! Furthermore, the less an adviser’s portfolio followed common sense investing rules, the worse off her clients’ portfolio performance tended to be.

The study found that most of the financial advisers made terrible investment decisions for themselves, and then went on to inflict these poor investment behaviors on their clients. In fact, the study finds that the adviser’s trading behavior turned out to be the best predictor of clients’ trading behaviors. For example, advisers who used the most expensive funds had clients that did the same and vice versa. In fact, clients who moved from one adviser to another tended to start trading in synch with their new counsel. The study suggests that if you want to know about an individual’s personal financial decisions, the best place to look is in the portfolio of the person’s adviser.

Some might argue that financial advisers should at least get credit for “practicing what they preach” in terms of financial advice. But the results of the study emphasize that you shouldn’t discount the possibility of conflicts of interest for advisers, on account of the financial incentives to sell certain products, as well as advisers being sincerely misguided in their views of personal finance.

This study, which examines data from 1999 to 2013, is aptly named “The Misguided Beliefs of Financial Advisors.” It was written by Juhani Linnainmaa, Associate Professor of Finance and PCL Faculty Scholar at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business; Brian Melzer, Assistant Professor of Finance at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of management; and Alessandro Previtero, Assistant Professor of Finance at the Indiana University Kelley School of Business. The three used data provided by three major Canadian financial institutions.

The Findings

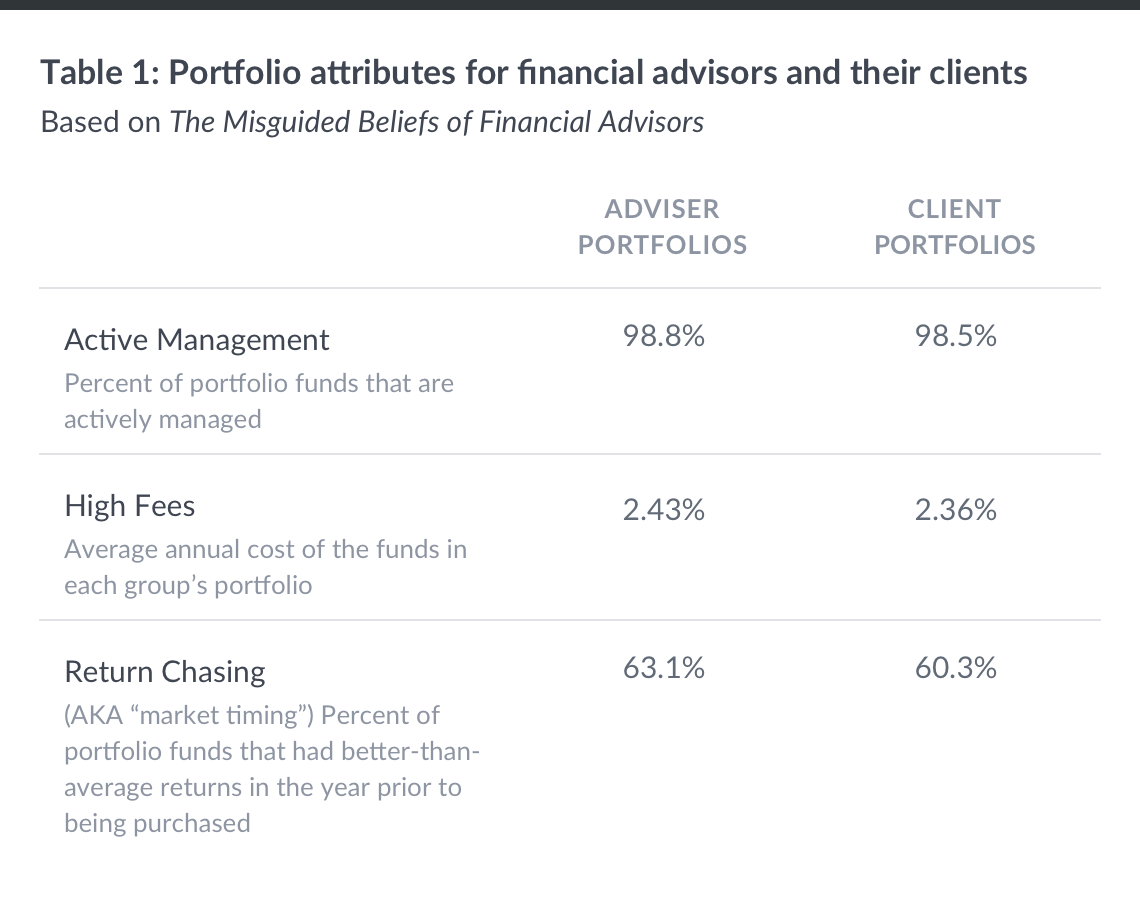

The table below summarizes some of the study’s findings on the characteristics of the portfolios of these financial advisers as well as those of their clients. In every case, the two were strikingly similar.

High Fees

The first two areas, active management and high fees, are closely related. Both sets of portfolios had nearly 99% of their funds invested in actively managed funds. And these funds are expensive, with annual fees that average close to five times the cost of a passively managed index fund.

This is a double-whammy of bad advice, as we explained in our blog post “The Tyranny of Compounding Costs.” First, the before fee returns of actively managed mutual funds are indistinguishable from their much-less-expensive counterparts. Second, that price difference adds up dramatically over time. A 35-year old who invests only in passively managed funds will, at age 85, have nearly double the portfolio of a 35-year old taking the more expensive route.

Timing the Market

Because Wealthfront believes that markets are fundamentally unpredictable in the short run, one of our core principles is that investors shouldn’t try to predict when the market will be up or down, but instead take a “set it and forget it” approach to investing. (See “The Cost of Chasing the Market.”)

But the study tells a different story. Instead, roughly 60% of the investments in a given year had better-than-average returns in the year prior to them being included in a portfolio, clear evidence that investors were trying to time the market. If there were no attempts to time the market, we would expect this pattern to only happen 50% of the time.

Our own study of Wealthfront portfolio owners who attempt to chase returns showed they do substantially worse than those who calmly sit out the market’s inevitable ups and downs.

We’ve Seen This Movie Before

The results presented in this paper indicate that a considerable portion of financial advisers appear to have misguided beliefs about what constitutes as sensible investment advice. And this is hardly the first study to point out their shortcomings. One study noted that advisers prefer expensive products to less costly ones with equal or better performance. Another study concluded that participants in an Oregon retirement plan for university employees would have done better without any advisers at all.

At Wealthfront, we avoid the pitfalls mentioned above. We invest our clients’ hard-earned money in diversified, low-fee portfolios of ETFs, which we automatically rebalance at no commission cost. On top of this, we offer a tax-loss harvesting and a new approach to financial planning at no incremental fee.

If you are not quite ready to join us, next time you meet with your traditional financial adviser, make sure to ask them three questions. (A) Do your own investments reflect the principles of low-fees, no market chasing, and diversification? (B) Are you acting as a fiduciary? (C) Are you Canadian?

Hint: The last one should be the least of your concerns.

Disclosure

Nothing in this blog should be construed as tax advice, a solicitation or offer, or recommendation, to buy or sell any security. This blog is not intended as investment advice, and Wealthfront does not represent in any manner that the circumstances described herein will result in any particular outcome. While the data Wealthfront uses from third parties is believed to be reliable, Wealthfront does not guarantee the accuracy of the information. Investment advisory services are only provided to investors who become Wealthfront clients. For more information please visit www.wealthfront.com or see our Full Disclosure.

About the author(s)

Pedro Olea de Souza e Silva is a Senior Quantitative Researcher at Wealthfront. His work mainly focuses on applying economic modeling and quantitative data analysis to Wealthfront’s financial planning experience. He earned a PhD in Economics from Princeton University where he studied behavioral economics. Prior to Princeton, he received an MS in Economics from the Getulio Vargas Foundation, and a BS in Economics from the University of Sao Paulo, both in Brazil. Andy Rachleff is Wealthfront's co-founder, President and Chief Executive Officer. He serves as a member of the board of trustees and vice chairman of the endowment investment committee for University of Pennsylvania and as a member of the faculty at Stanford Graduate School of Business, where he teaches courses on technology entrepreneurship. Prior to Wealthfront, Andy co-founded and was general partner of Benchmark Capital, where he was responsible for investing in a number of successful companies including Equinix, Juniper Networks, and Opsware. He also spent ten years as a general partner with Merrill, Pickard, Anderson & Eyre (MPAE). Andy earned his BS from University of Pennsylvania and his MBA from Stanford Graduate School of Business. View all posts by Pedro Olea de Souza e Silva, PhD and Andy Rachleff