Editor’s note: Interested in learning more about equity compensation, the best time to exercise options, and the right company stock selling strategies? Read our Guide to Equity & IPOs

IPOs get all the press, yet it’s far more likely a startup employee will experience an acquisition. Unfortunately very little has been written about how an acquisition affects the average tech worker financially. With all the recent news of multi-billion dollar acquisitions, it’s too easy to forget that not every acquisition leads to a windfall for its employees.

In my experience there are four types of acquisitions:

- The Fire Sale

- The Acqui-hire

- The Modest Price

- The Exceptional Price

Each acquisition type leads to very different outcomes for the employees.

The Huge Role of the Liquidation Preference

Before describing the different types of acquisition outcomes employees might experience we first need to explain liquidation preference, a term of the Convertible Preferred Stock issued to venture capitalists that plays a crucial role in the distribution of acquisition/merger proceeds among investors and employees.

In How Do Stock Options and RSUs Differ?, we explained how venture capitalists came to acquire Convertible Preferred Stock in startups so as to enable stock options to be priced at a fraction of the price they paid. In order to justify a lower price for stock options to the IRS, the Convertible Preferred Stock issued to the venture capitalists had to appear more valuable than the Common Stock issued to employees. I say appear because it was highly unlikely the Preferred Stock’s unique rights would ever come into play.

Participating Preferred: The Double Dip

Liquidation preference was one of the critical terms designed to create the illusion of greater value for the Convertible Preferred Stock. Liquidation preference grants the investors preferential rights (thus the term Preferred Stock) in the case of the sale of the company. It can take one of two forms, straight, more commonly known as classic, and participating. Classic preference grants investors the right to choose whether to have all their invested money returned or to have it converted into common stock and thus receive a share of the proceeds equal to their ownership stake. Because the investors have preference, they receive all proceeds in a sale that values their company at less than the amount invested.

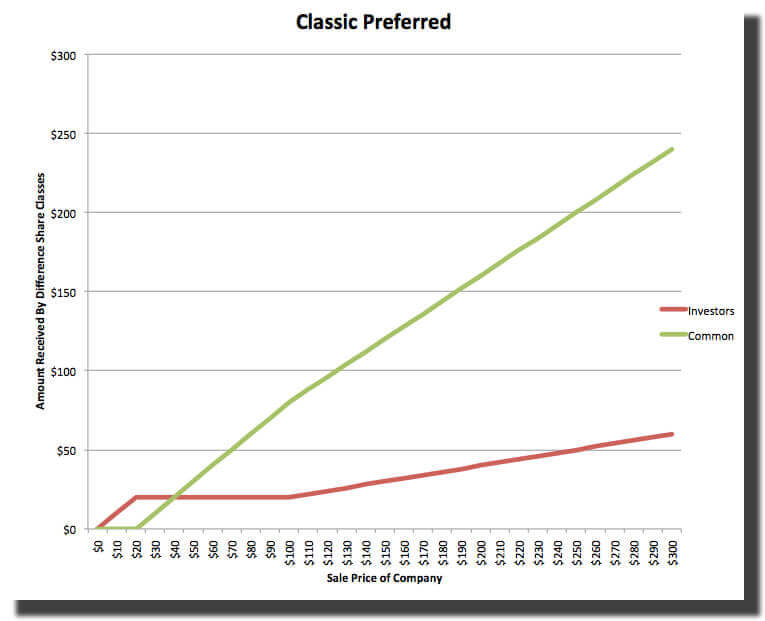

Let’s look at a classic preference example. If venture capitalists and angels collectively invested $20 million for a 20% stake in a company that is sold for $200 million, the investors have the right to either get their $20 million back — or convert to Common and get 20% of the proceeds which in this case equals $40 million. The Common shareholders, which include stock option and RSU holders, would share the remaining proceeds proportionally or pro-rata.

The graph below displays the amount of money Investors and Common shareholders would receive at different acquisition values. The Investor line has a slope of 1.0 below $20 million because the investors get all the proceeds up until that point. The Investor line then flattens from an acquisition price of $20 million to $100 million because the Investors would opt for their $20 million of preference and the remainder would go to the Common shareholders (thus the slope of 1.0 for the Common curve between $20 million and $100 million). Above $100 million, the Investors would convert, so the slope of their line changes to 0.2 (the percentage of the proceeds they would receive).

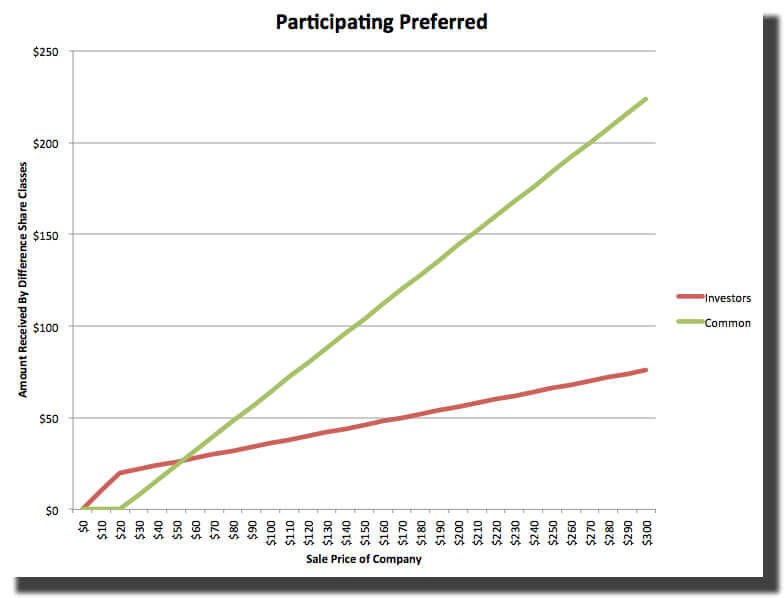

With participating preference the investors receive the right to get their money back and share in the remaining proceeds according to their ownership. Using the previous example, in the $200 million scenario the investors would receive $56 million ($20 million plus 20% of $180 million) and in the $100 million sale scenario they would receive $36 million ($20 million plus 20% of $80 million). Because participating preferred gets their money back first and shares the remainder pro-rata, it’s often referred to as a double-dip (it’s intended as a pejorative term because it’s considered excessively generous to the investors).

In the graph below you can see how in the participating case the Investors receive incrementally more money as the acquisition price increases. The rate of the increase drops from 100% of the incremental proceeds to 20% once an acquisition price of $20 million has been reached.

It’s possible for employees to get far less than their expected ownership stake when the preference clause is triggered. That’s because they only share what remains after the preference has been distributed to the investors. Let me use an example to illustrate. Say you’re an engineer who works for the company that raised $20 million for a 20% ownership stake with a participating preferred. That means the employees collectively own 80% of the company. If the company were sold for $100 million, $36 million would be allocated to the investors (as we explained above) and $64 million to the employees. Our engineer would get her pro-rata share of the proceeds available to the employees, which would equal $400,000 ($64 million x 0.5%/80%). That’s 20% less than the $500,000 she expected based on her ownership percentage (0.5% x $100 million). As you can now see the amount of money an employee can expect to receive in an acquisition is not only based on her ownership percentage, but the company’s sale value, amount invested and whether or not her company was able to avoid participating preferred (it should be noted that like all other convertible preferred stock terms, liquidation preference goes away once a company goes public).

Acquisition Outcomes Explained

The Fire Sale

The first and most dreaded type is the fire sale. This usually takes the form of an asset sale, meaning the acquirer buys the company for its assets (intellectual property, distribution relationships, customer base) rather than its ongoing business. Asset sales are usually valued below the amount of money invested in the business, which results in the investors receiving all the proceeds because of their liquidation preference. The only employees who receive anything in this case are a few senior members of management who typically receive a small share (less than 10%) of the proceeds from the investors as an incentive to stick around and get the company sold. Seldom do rank and file employees ever see any money in this scenario. To make matters worse few of the employees are retained in this kind of acquisition because the acquirer doesn’t intend to maintain or grow the acquired business.

The Acqui-hire

An acqui-hire is a type of acquisition used to recruit coveted employees rather than add a new line of business. An acqui-hire typically only occurs when a startup fails to build a business and has run out of money. The founders are willing to join the acquirer to save face, find a soft landing for their employees and earn a reasonable amount of money over a short period of time. Most acqui-hire acquisitions are consummated before a startup has raised venture capital and are usually valued at less than $10 million.

To illustrate, an acquisition offer of $6 million can be very attractive if a startup has eight sought-after employees, has raised $1 million from angels, is about to run out of money and hasn’t found product/market fit. In this scenario the angels would get their $1 million back and the acquirer would allocate the remaining $5 million across the eight employees according to how valuable they might be to the acquirer.

Perhaps the most important issue for you to determine when joining a company — if major financial success is a top consideration — is your potential employer’s rate of momentum. The fastest growing companies have the highest odds of going public or getting acquired in the exceptional scenario.

Often acquirers use acqui-hires to hire people they otherwise couldn’t attract given the constraints of their equity compensation plans. Equity distributed in an acqui-hire is often a few times as large as what an employee could expect to receive if she joined the acquiring firm through the normal recruiting process. In some instances vesting schedules will be lengthened as part of the acquisition and/or additional options might be issued. Once an acqui-hire is consummated the newly acquired employees are likely to be re-assigned to projects of interest to the acquirer, not the projects on which they were working which might not be to their liking.

The Modest Price

In this scenario the acquirer pays a price that may range from $50 million to $300 million. This can be attractive, from a financial perspective, for the rank and file employees depending on how much capital has been raised and whether participating preference was granted. The less capital raised the better for the employees. In this scenario the acquirer often issues additional equity to the most valued employees to ensure they stick around for a while. These additional grants are often known as golden handcuffs.

Options issued to employees who work for the acquired company are converted into options of the acquirer. The proportion of the option exercise price to the acquisition price is maintained in the newly converted options to purchase the acquiring company’s stock.

For example, let’s say a senior engineer had an option to purchase 75,000 shares of the acquired company’s stock for $0.50 per share and the acquisition price is $4.00 per share in the form of Common Stock. Let’s further assume the acquirer’s stock is priced at $24 per share. The engineer’s options would be converted into an option to purchase 12,500 shares of the acquirer’s stock at an exercise price of $3.00 per share. You’ll notice the engineer’s profit remains the same despite the change in shares and exercise price.

The employee vesting schedules usually carry over into the new company. By that I mean that an employee who was 50% vested before the acquisition will be 50% vested in the new company. Sometimes employees receive a slight acceleration in their vesting upon acquisition, but usually only if their jobs were eliminated as part of the acquisition. Companies that are acquired for a modest price are often folded into existing operations run by the acquiring company, which implies less autonomy than as an independent company.

The Exceptional Price

The last scenario is the case where the acquiring company pays what many consider an outrageous price to buy a company that is of great strategic value. Instagram, YouTube and WhatsApp are classic examples of this type of acquisition. We explained the economics of the WhatsApp acquisition in great detail in WhatsApp: What an Acquisition Means for Employees. In this case the acquisition price is so high that liquidation preference has little or no impact on the economics for the acquired employees. The acquired employees still have to vest their stock and are usually granted tremendous autonomy because any company that can command a billion dollar price can secure a great deal of independence as a term of the deal. In many of the outrageously priced deals employees are given additional incentives in the form of stock options or RSUs to ensure they stick around. The logic is that if the acquirer paid a huge price then it would be penny wise and pound foolish not to issue additional incentives to make sure that key people remain.

What can you do to protect yourself?

In The 14 Crucial Questions About Stock Options we listed a number of questions you should ask about your offer to give you the best odds of faring well in an acquisition. All of the critical issues described in this post, including liquidation preference, amount of capital raised, how long the money will last and vesting acceleration, were addressed (and often in much more detail).

Perhaps the most important issue for you to determine when joining a company — if major financial success is a top consideration — is your potential employer’s rate of momentum. The fastest growing companies have the highest odds of going public or getting acquired in the exceptional scenario. That’s one of the reasons why we so highly recommend joining a rapidly growing mid sized company, especially early in your career.

About the author(s)

Andy Rachleff is Wealthfront's co-founder and Executive Chairman. He serves as a member of the board of trustees and chairman of the endowment investment committee for University of Pennsylvania and as a member of the faculty at Stanford Graduate School of Business, where he teaches courses on technology entrepreneurship. Prior to Wealthfront, Andy co-founded and was general partner of Benchmark Capital, where he was responsible for investing in a number of successful companies including Equinix, Juniper Networks, and Opsware. He also spent ten years as a general partner with Merrill, Pickard, Anderson & Eyre (MPAE). Andy earned his BS from University of Pennsylvania and his MBA from Stanford Graduate School of Business. View all posts by Andy Rachleff